An article by Andrew Roberts, May 2012

On hearing about the release of the latest Selmer Saxophone, a player went into his local dealer in Copenhagen to try this shiny new model. Having tried it in the shop, he asked if he might take it away on approval and the shop owner agreed a week’s trial period.

Cycling home (as many do in Copenhagen) with the saxophone on his back a truck went by him so close he had to swerve to avoid collision resulting in him taking a tumble off his bike. Sadly he discovered, that although he was OK, the saxophone was not. In fact it was flat – not in pitch – it was no longer a tube!

Horrified, he decided to return the sorry instrument to the shop the next day. On explaining what had happened to the shop owner, he was surprised when the owner laughed as the damaged case was opened to reveal the tragedy. Having offered to pay for the damage, the shop owner said it wouldn’t be necessary and he brought out a new one for the player to take on a week’s approval again.

Imagine the players surprise when he returned to the shop a week later to find the flat saxophone in the shop window, above it a sign that read: “ Blow don’t suck!”

This true story nicely illustrates my point of view on testing woodwind instruments. The use of suction to test is a tried and tested method for checking the airtight seal of wind instruments used by many repairers, which everyone can master, but it has a major disadvantage.

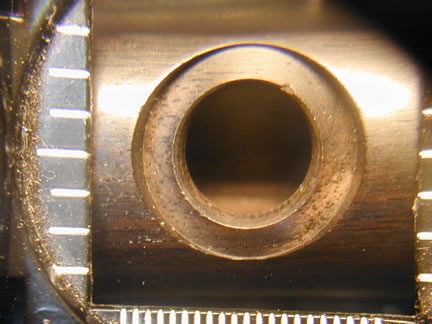

By creating a vacuum by sucking the air out of the clarinet, any loss of suction can be felt, but as a test of the seal, which the pad is making with the tone hole, it is off little use. The reason is simple sucking the air out of the body of the clarinet causes any design of pad surface to be pulled onto the tone hole surface. This would be fine if the surface of the tone hole were completely flat and did not have any flaws from the manufacturing process. A photograph of a clarinet tone hole magnified should speak a thousand words.

By creating a vacuum by sucking the air out of the clarinet, any loss of suction can be felt, but as a test of the seal, which the pad is making with the tone hole, it is off little use. The reason is simple sucking the air out of the body of the clarinet causes any design of pad surface to be pulled onto the tone hole surface. This would be fine if the surface of the tone hole were completely flat and did not have any flaws from the manufacturing process. A photograph of a clarinet tone hole magnified should speak a thousand words.

Even the best pads cannot give a fully air tight seal on a surface like this.

Why, you might ask, is the surface so poor? These flaws can be from the naturally open wood grain, which can move during use, or the poor cutting of the tone hole in production where the tone hole cutter may have become blunt and has chattered chunks out of the wood rather than cutting cleanly.

Sadly, despite most players believing their beloved instrument has been the result of the loving care one might have expected from a hand made instrument, the reality is that all clarinets are made (with a very small number of exceptions) in mass production.

Even the most expensive models are produced, not in days as we might have expected, but in roughly 3-4 hours. There is simply no room in the production schedule to allow for the care and attention to detail that we might like to believe our instrument has undergone during its birth.

Clarinet players have allowed manufacturers to get away with this for decades with the result that few clarinet players have felt the benefit of a 100% airtight instrument. As more players have the opportunity to play on totally airtight instruments, clarinet manufacturers may well come under increasing pressure to up their game – until then they will continue to get away with it.

Many clarinettists are shocked to find that they have to consider putting right the many flaws that result from the mass production instruments, as they believe their instruments are expensive enough. However, a quick survey of the cost of other instruments should highlight the fact that we have had the bargain basement price for our instruments for a long time. A good professional flute will cost a minimum of £6,000 – for one!

As their instrument is so much less efficient than the clarinet, flute players know they will have to pay more to get even the smallest improvement or advantage over others. As a result they have demanded more of the makers and repairers and have accepted that bespoke work will cost more but have found the results worthwhile.

Some clarinet players are happy when their instrument just makes a sound, even if it is hard work and unreliable. There is almost a pride in being able to make a sick instrument work, which is bizarre really. Those of us with a less masochistic approach to life with the clarinet can appreciate the differences that a truly airtight instrument can provide. A 100% airtight seal is possible and demonstrable.

An airtight seal affects every aspect of the instrument’s behaviour, being able to play from nothing to a trumpet like fortissimo is one, and effortless altissimo notes another, but one lesser-known aspect is the effect on the tuning of the instrument. The loss of air in the tube of the clarinet equates to a loss of energy and means the player will need to input more energy to maintain the sound output – a bit like having a small but significant leak in the fuel tank of your car, it will keep going but it will be less efficient and will cost you more if the leak isn’t fixed.

An instrumental sound is made up of partials, or harmonics, and these are the key to a full and focussed sound, which gives true projection. Volume is not the only consideration in making a sound carry to the back of a large hall, harmonics or resonance are the reason why a singer can produce a sound from a human body which can be heard above a 90 piece orchestra at full tilt. Harmonics are produced in the resonance of the body of either a human or an instrument. When a wind instrument is completely airtight it produces a wide spectrum of, in the clarinet’s case, odd harmonics which help to give it projection.

Here is a simple example of how a clarinet that is not airtight immediately looses harmonics. The lowest note E will work, even though the crows foot adjustment on the low E/B is not correct. However, the next harmonic up, B (with the register key added to the low E and the appropriate air speed used) won’t work. Imagine then how many harmonics, or how much resonance is lost over the whole instrument when it is not airtight?

A Magnahelic testing machine specially constructed for the purpose of testing wind instruments provides the technician with precise information about the percentage of air loss in the body of a wind instrument. It works by applying a constant and adjustable (depending on the instrument tested) low pressure of between 1-3 psi, which is the maximum pressure of air a wind player can produce. The key to the accuracy of the result is a pressure release system, which is calibrated to not blow open reasonable spring pressures of the closed keys. Players should need no more than their natural finger weight to make a pad closure on a clarinet.

The Magnahelic gauge gives a calibrated result of the loss of air in the instrument. Typically a brand new factory instrument will loose between 20-30% of its seal, some instruments can have close to no seal and still “work”, to a point. Using this system it is possible to make an instrument 100% airtight, anything less is rather pointless. Give a flute player a flute that has a 20-30% loss of airtight seal and they would hand it back saying it doesn’t work at all.

As the flute is much less efficient with its use of air, flute players notice even the smallest changes to the efficiency of their instrument. The clarinet in comparison is far more efficient so the loss of efficiency is not so readily recognised, until they play on a 100% airtight clarinet, they can continue in ignorant bliss.

A significant advantage of the Magnahelic blow test is when the pads are not the cause of the leak. Frequently air can escape through parts of the body such as pillars or more commonly speaker/thumb tubes. Using a pressurizing system makes it easy to detect where the air loss is, something the vacuum method cannot achieve as it can only show a loss and not its position. Combined with the advantage of knowing that the closed pad is not lifting under reasonable air pressure, creating air loss, it represents the sensible choice from a scientific and engineering approach.

Clearly the use of a Magnahelic machine is not something available to all, but its use in the professional workshop has clear advantages and means that during your visit to the workshop you can have a visual confirmation that your instrument is being returned to you in a fully airtight condition.* You pays your money and makes your choice – as they say!

*To find out more visit www.theclarinet.co.uk/arcs